Key Takeaways:

- By carefully choosing the right unit of measurement and target, the parties can collect contract data that drives future performance.

- Metrics, especially those tied to incentives and liquidated damages, have to be reasoned, reasonable, achievable, and limited to just a few.

- When drafting metrics to monitor supplier performance, start with the buying company’s business objective.

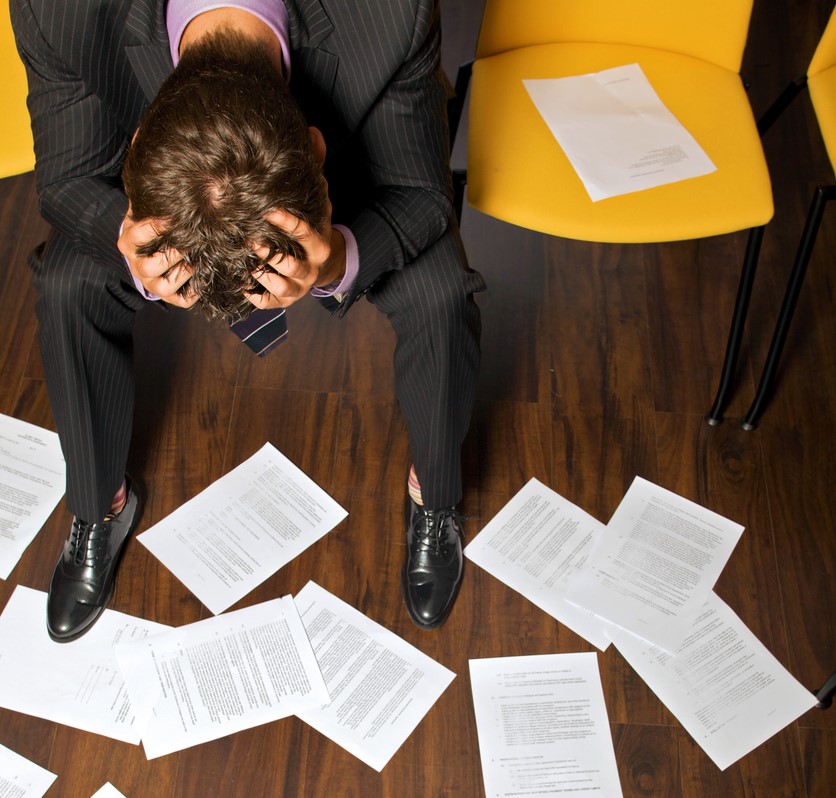

Would you like to know the ugly truth about performance scorecards? Most scorecards do not tell companies what their stakeholders want to know about a supplier’s past performance to drive meaningful future performance. Since stakeholders need to know about their suppliers’ performance, buying companies establish scorecards that track performance measures (e.g. metrics). Buying companies then use metrics to levy remedies in the form of service credits or liquidated damages in the face of deficient supplier performance. But, stakeholders may complain about repeated performance failures in spite of using a scorecard and collecting service level credits.

Do your performance-based contracts have meaningful metrics? Do the metrics drive future performance or do stakeholders feel frustrated that what is being measured is not meaningful to them?

This article will help you craft much more effective performance scorecards. I will highlight two mistakes to avoid and provide some example contract metrics you should consider including in your next scorecard.

Two Mistakes to Avoid

There are two reasons why scorecards miss the mark. One, buying companies choose the wrong unit of measurement and, two, they set the wrong performance target. In essence, the parties are collecting a lot of information, but that information does not drive future performance.

Think about your organization’s requests for metrics and a scorecard. Is your company using basic metrics across an entire category despite the type of work a specific supplier performs? A typical performance scorecard is similar to a photo—a snapshot at one point in time. What that photo captures may not be useful to drive this supplier’s performance. This is particularly problematic when using a standard template scorecard for a specialized service.

Organizations that want to drive specific supplier performance, should draft specific metrics or create scorecards with a mix of standards and specific measures. When drafting objective performance measures, the measures should leverage historical data topredict forward looking insights that help the parties manage risk and meet the buying companies’ business objectives.

Getting Performance Right

Just because we can measure something does not necessarily mean that we should measure it. Metrics establish the agreed-upon performance standard when compared to actual performance. When establishing performance measures, those measures should be:

- Reasoned meaning well thought out and directly pertaining to the customers business objectives. (Learn more about drafting business objectives here How to Draft Better SOW Requirements).

- Reasonable meaning using the industry’s established standard, and a history of this supplier meeting the industry standard.

- Achievable means that the supplier is empowered to achieve the established performance measure. I’ve too often seen situations where the supplier is not empowered to achieve the standard, usually in the form of customer interference or a third-party supplier’s interference.

- Limited means only a few key measures that drive needed results without over-prescribing how the supplier meets the results.

In most instances only a handful of metrics are appropriate for any given contract. To pick the right actions to measure, consider the benefits of meeting each metric in furtherance of meeting the customer’s business objectives. In other words, the supplier’s performance must directly relate to enhancing the business objectives. Second, the parties must track performance that falls within the supplier’s span of control to hold suppliers accountable for meeting performance.

Example Meaningful Metrics

For example, an executive is flying from Seattle to New York City with a stopover in Chicago. In order to know if the executive will make it to New York on time, they might choose to track the timing of various points along the flight path. However, the most critical interim milestone is the time the executive lands in Chicago because if they are late, they run the risk of missing their flight to New York City. Therefore, a meaningful metric would track the time the plane lands in Chicago against the time the flight to New York City departs.

Some people might think they need to track each 50-mile leg of the flight from Seattle to New York City to get to New York City on time. Flights can makeup time in the air, so a delayed departure from Seattle may have no impact at all on the landing time in Chicago. Therefore, tracking to incentivize or penalize the arrival time in Chicago is the meaningful metric tied to the business objective of getting to New York City on time.

Since departing Chicago on time for New York City is the objective, tracking each 50-mile leg of the trip as a metric may overburden everyone resulting in loss in focus of the true objective—. On the other hand, collecting data without incentives or penalties on each 50-mile leg of the Seattle to Chicago flight helps the executive monitor and course correct by choosing a better time of day to depart Seattle to depart on-time from Chicago.

Performance Scorecard: Drafting Tips

- Start with the business objective. Depart Chicago for New York on time.

- Identify the industry-wide performance standard. Look at the industry average for on time departure times for each airline at Chicago, O’Hare airport at the time of day for the connecting flight to New York. For example, one airline might have a 75% on time arrival from Seattle, while a competitor has a 90% on time arrival from Seattle. In supplier selection, you would choose the airline with a 90% on-time arrival.

- Identify the allowable deviation tolerance from the standard. The flight to Chicago may deviate up to 20 minutes late to still be considered “on time”.

- Identify the liquidated damages for a deviation of greater than 20 minutes. A deviation of 30 minutes later than the published on time arrival from Seattle may incur a verifiable cost of $25. However, missing the flight to New York City, may incur a verifiable cost of $1,000.

- Determine which organization will collect the data, how the parties will validate the data, and how often the data needs to be collected.

Are you intrigued to learn more? Stay tuned. Each month right here, I will provide more information to help you draft, negotiate, and manage performance-based contracts. If you want the manual to learn at your own pace, purchase your copy of The Contract Professional’s Playbook: The Definitive Guide to Maximizing Value through Mastery of Performance- and Outcome-Based Contracting.